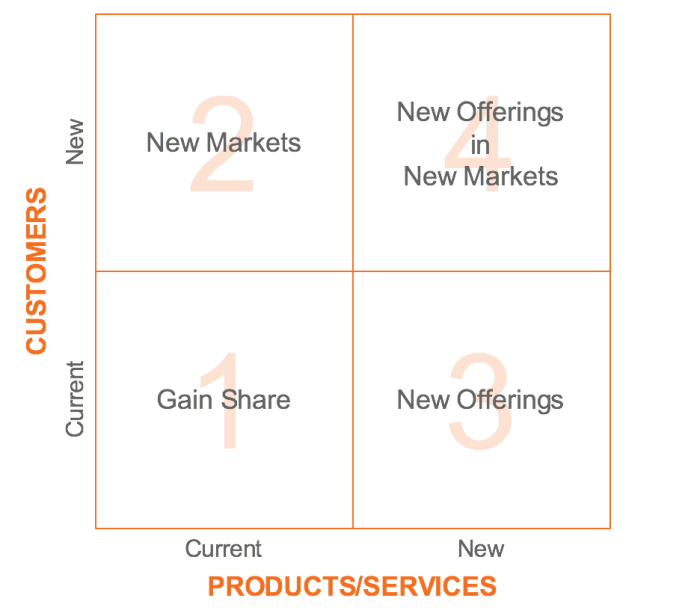

In Your Innovation Roadmap, Part 1, I introduced the innovation matrix (featured above) and covered Quadrant 1: gaining market share. In Part 2, I covered Quadrant 2: bringing your current offerings to new customers. In Part 3, I covered Quadrant 3: bringing new offerings to existing customers. And, in Part 4, I covered what context to keep in mind in deciding whether or not to pursue Quadrant 4: bringing new products/services to new customers.

In this post, I’ll share two well-known innovation processes and similarities between them, so that you can begin to craft an innovation process that is right for your organization and culture. I’ll also point you to several other innovation approaches that you can dive into deeper.

INNOVATION PROCESSES

Over the last decade, since startups entered the zeitgeist of our aspirational culture, there has been a lot of hype around new approaches and processes that can drive innovation for your startup or enterprise corporation alike. “Just follow this one approach and your innovation initiative will be a huge success!” they spout, persuading eager innovators-to-be to take up their movement. Many of these innovation approaches have been tried and tested by entrepreneurs and executives that now wish to share their wisdom, while others are crafted by consultants and intellectuals who are selling that approach as part of their services. Regardless, I believe that no single approach is right for every organization. But, I do believe that each can serve as a tool in the proverbial ‘innovation toolbox’, so that an organization can test and learn their way into an approach that fits with their culture. Below, I’ll cover two well-known innovation approaches that I have found useful.

Also, important to note is the fact that attempting to teach these techniques via a blog post would not do them (or you) justice. Thus, my goal here is to give you a high-level understanding of the approach and point you in the direction of material that explains these approaches, and others, in much more depth.

The Lean Startup

The Lean Startup, written by entrepreneur and consultant, Eric Ries, introduces the concept of validated learning, which Ries describes as follows:

“Validated learning is the process of demonstrating empirically that a team has discovered valuable truths about a startup’s present and future business prospects. It is more concrete, more accurate, and faster than market forecasting or classical business planning.”

The Lean Startup method applies the lean manufacturing management philosophy that was made famous by the Toyota Production System to startups. The philosophy aims at discovering and eliminating all wasteful activities, and, thus, leaving and focusing only on value-creating activities. Value is defined from the customer’s perspective. Value provides a benefit to the customer; the customer must be willing to pay money for it. Anything else is waste. In the context of a new venture (or ‘startup’), any activities that do not contribute to learning what a customer sees as value are wasteful. As an organization learns more about what its customers recognize as value, it can develop and sell a product that can sustain a business through those customers. Thus, Ries argues that validated learning is the core unit of progress for new ventures; validated learning always achieves positive improvements in the new venture’s key metrics. So, how do we pursue validated learning? Through the scientific method.

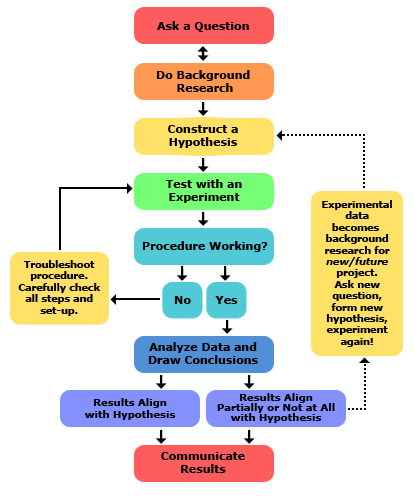

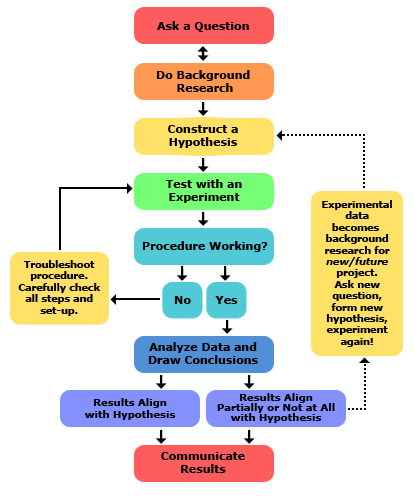

For those that don’t remember the scientific method from grade school, it is a process of experimentation that is used to explore observations and answer questions. The process goes as follows:

The Lean Startup borrows from this, arguing that the two most valuable assumptions that an entrepreneur can make are:

- The value hypothesis, which tests whether or not the product/service really delivers value to customers once they are using it.

- The growth hypothesis, which tests how new customers will discover a product/service

Once the entrepreneur makes these assumptions/hypotheses, she can craft an experiment to test them. Ries argues that in the Lean Startup, an experiment is the first product. This is a departure from typical, wasteful corporate approaches to innovation, where they invest in long periods of R&D or product development to build a new product, release it to the market and find that customers aren’t willing to pay for it. Instead, in the Lean Startup, product/service development becomes an iterative process of testing and learning your way into a product that is valuable to your customers. This method is captured in the Lean Startup process of: Build –> Measure –> Learn.

In the Lean Startup, the first product (read ‘experiment’) you build is called the minimum viable product (or ‘MVP’). This product is merely an experiment to validate the idea behind the venture: is there demand for the product/service offering, and are customers willing to pay for that offering? Ries gives the example of how Drew Houston, the founder of Dropbox, used a video as their MVP. The video gave a 3-minute faux demo of the Dropbox product before the product was even built. This video grew Dropbox’s beta waiting list from 5,000 people to 75,000 “literally overnight.” It was a simple way to validate whether or not there was demand for the product before investing the time and money to build it. Ries gives several other examples of MVPs, but the key thing to keep in mind when building your MVP is to: “remove any feature, process, or effort that does not contribute directly to the learning you seek.” Then, measure and learn from that experiment, and craft your next hypothesis and experiment to continue the validated learning process.

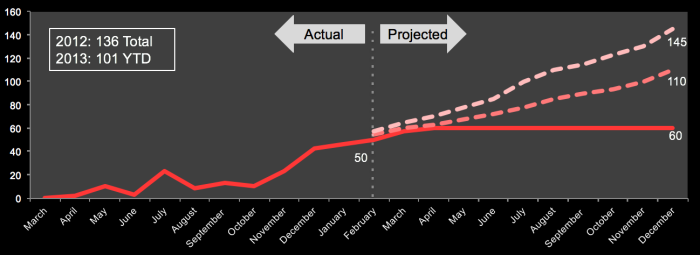

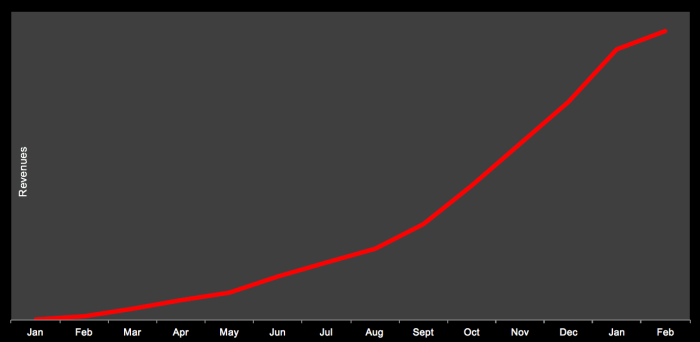

Lean Startup techniques can be applied to a variety of companies, industries and projects. For example, I used Lean Startup methods while at W2O Group to grow a new and relatively small account (Verizon, which started as a $245K project) to $2M revenues in 2012 and to $5.5M in revenues in 2013, turning Verizon into W2O’s largest account at the time.

We were hired to build a custom social media analytics platform for Verizon, but didn’t have the technological acumen yet. We had one developer and one project manager that still worked off of waterfall development techniques (the PM’s original timeline to deliver an alpha product to Verizon was along the lines of six to nine months!) and no designers, UI or UX practitioners that could create meaningful data visualizations. But, we did have analysts – over sixty of them. So, we quickly pivoted from focusing on the dashboard timeline to focusing on delivering PowerPoint reports from the analytics that we would eventually visualize automatically through the dashboard. The PowerPoint reports were our MVP. And, they sold like hotcakes.

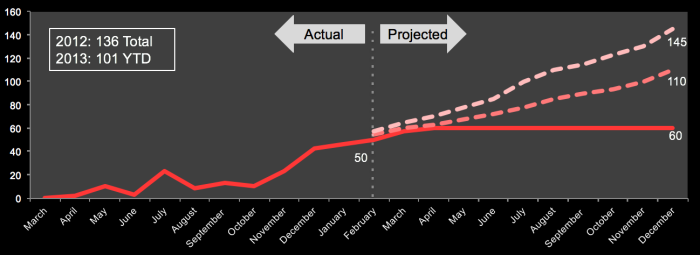

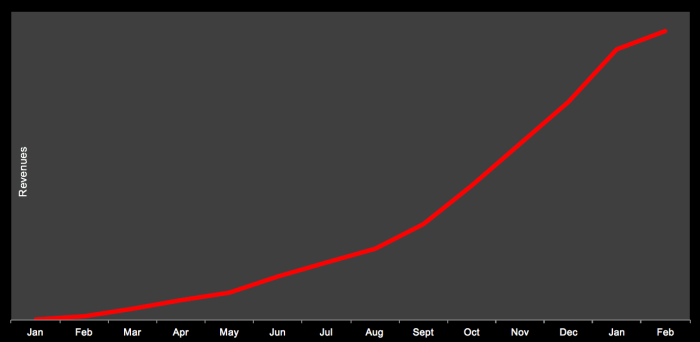

Below are two snapshots of our hockey stick growth. The first chart shows the number of reports that we delivered per month across Verizon in the first twelve months, while building the analytics platform in parallel, as well as our low, medium and high projections for future demand of reports. The second chart reflects revenue growth in the first twelve months.

The analytics product that we built for Verizon then served as our MVP for a new SaaS version that W2O could offer across clients. A newly hired developer, John Steinmetz, and I saw that W2O was building these custom dashboards for other clients, and W2O was losing its shirt because of its consulting/hourly fees-based business model. So, we worked on the side to build a SaaS version. The product launched under the name Footprint and achieved over $1.3M in revenues in its first year. Steinmetz did an amazing job bringing this idea and product to reality.

In his book, The Lean Startup, Ries provides much more in depth techniques and case studies for how to achieve validated learning, including those that apply to large organizations. For example, Ries references how Intuit holds itself accountable for innovation through two KPIs (key performance indicators):

- The number of customers using products that didn’t exist three years ago, and

- The percentage of revenue coming from offerings that didn’t exist three years ago

I highly recommend reading The Lean Startup, so you can see how to apply its approach to your business.

Design Thinking

Design Thinking has been getting a lot of buzz over the last five years or so, as large companies are now looking to establish their innovation engines to compete with the startups that are ripe to disrupt them. Having seen Apple‘s success in becoming the most valuable company in the world primarily through launching wonderfully designed products, CEOs are hungry for their own design forward innovation. IDEO and frog are perhaps the two most well-known players in this space, consulting organizations on assimilating Design Thinking into their daily activities. Both have worked with Apple since the early years. And, IDEO more recently counseled IBM in creating their Design Thinking approach, which you can find here.

Design Thinking is a method for innovating routinely. It puts customers at the forefront through empathy. The goal is to empathize with the customer, which often starts with behavioral observation. What are they doing? How are they doing it? Why are they doing it? But, ultimately needs to move to understanding people’s motivations and core beliefs.

Each innovation program must align across three factors:

- PEOPLE: is the offering desirable by the target audience (customer)?

- TECHNICAL: is the offering technically feasible with today’s technologies?

- BUSINESS: is the offering economically viable within a business model?

Finding the sweet spot between desirability, feasibility and viability is what IDEO and the Stanford d.school define as Design Thinking.

This method follows a four-step process: Inspiration –> Synthesis –> Ideation/Experimentation –> Implementation. IDEO partner, Chris Flink, wrote an excerpt explaining their Design Thinking approach in the book Creative Confidence, written by IDEO co-founders, Tom Kelley and David Kelley. That excerpt is highlighted below:

“INSPIRATION

Don’t wait for the proverbial apple to fall on your head. Go out in the world and proactively seek experiences that will spark creative thinking. Interact with experts, immerse yourself in unfamiliar environments, and role-play customer scenarios. Inspiration is fueled by a deliberate, planned course of action.

To inspire human-centered innovation, empathy is our reliable, go- to resource. We find that connecting with the needs, desires, and motivations of real people helps to inspire and provoke fresh ideas. Observing people’s behavior in their natural context can help us better understand the factors at play and trigger new insights to fuel our innovation efforts. We shadow and do interviews with a variety of people out in the field. We speak to ‘extreme users,’ for example, discovering how early adopters make clever use of technology. Or, if we are redesigning a kitchen tool like a can opener, we may observe how elderly people use it to look for points of frustration or opportunities for improvement. We look to other industries to see how relevant challenges are addressed. For instance, we may draw parallels between customer service at a restaurant and the patient experience at a hospital in order to improve patient satisfaction.

SYNTHESIS

After your time in the field, the next step is to begin the complex challenge of “sense-making.” You need to recognize patterns, identify themes, and find meaning in all that you’ve seen, gathered, and observed. We move from concrete observations and individual stories to more abstract truths that span across groups of people. We often organize our observations on an ’empathy map’ or create a matrix to categorize types of solutions. During synthesis, we strive to see where the fertile ground is. We translate what we’ve uncovered in our research into actionable frameworks and principles. We reframe the problem and choose where to focus our energy. For example, in retail environments, we’ve discovered that if you change the question from ‘how might we reduce customer waiting time?’ to ‘how might we reduce perceived waiting time?’ it opens up whole new avenues of possibility, like using a video display wall to provide an entertaining distraction.

IDEATION AND EXPERIMENTATION

Next, we set off on an exploration of new possibilities. We generate countless ideas and consider many divergent options. The most promising ones are advanced in iterative rounds of rapid prototypes— early, rough representations of ideas that are concrete enough for people to react to. The key is to be quick and dirty— exploring a range of ideas without becoming too invested in only one. These experiential learning loops help to develop existing concepts and spur new ones. Based on feedback from end users and other stakeholders, we adapt, iterate, and pivot our way to human-centered, compelling, workable solutions. Experimentation can include everything from crafting hundreds of physical models for delivering transdermal vaccines to using driving simulators for testing new vehicle systems to acting out the check-in experience at a hotel lobby.

IMPLEMENTATION

Before a new idea is rolled out, we refine the design and prepare a road map to the marketplace. Of course, rollouts can vary wildly depending on which elements of an experience or product are involved. Going live with a new online learning platform is very different from offering a new banking service. The implementation phase can have many rounds. More and more companies in every industry are beginning to launch new products, services, or businesses in order to learn. They live in beta, and quickly iterate through new in-market loops that further refine their offering. For example, some retailers launch pop-up stores as a way to test demand in new cities. And Boston-based startup Clover Food Lab began with a single food truck at MIT to gauge the market for its sustainable vegetarian food before the company committed to opening brick-and-mortar restaurant locations.”

Like Lean Startup, Design Thinking believes in an iterative approach to innovation. Its Three Rs of Prototyping – (1) Rough, (2) Rapid and (3) Right (referring to building several models/prototypes focused on getting specific aspects of a product right) – are not unlike Lean Startup’s concept of the MVP. At first glance, Design Thinking may seem more qualitative in its approach, where as Lean Startup seems more quantitative. But, if you dive deeper, they are quite similar.

For more information on Design Thinking, I recommend reading Creative Confidence, as well as perusing the d.school’s methods.

Other Innovation Processes

There are countless other innovation processes out there. The virtual aisles of Amazon’s Kindle library are filled with them. But, below are some that are worth a read:

Once you’ve read your way through these, I invite to you reference the Reading List page on this site, where I highlight other books, papers and articles that have impacted my thinking.

To read about Quadrant 1 – grow market share – click here.

To read about Quadrant 2 – new markets – click here.

To read about Quadrant 3 – new offerings – click here.

To read about Quadrant 4 – macro and micro context in bringing new offerings to new markets – click here.